Signalman Peter Key, Royal Corps of Signals

Died 4th October 1943

Peter Key was born in 1920 to Thomas Alexander and Hilda Annie Key. Peter’s father Thomas had been born in Clayton and lived at the Matsfield Arms (now The Jack and Jill pub) just by the entrance to Clayton Tunnel. The Matsfield Arms was also a Post Office and in the 1911 census it recorded Thomas as the telephonist. Peter’s grandparents ran the pub at that time.

Little is known of Peter’s life but his father Thomas was a member of Clayton Parish Council. Peter joined the Royal Corps of Signals, 18th Division Signals. It would seem that he was in the Far East, possibly Sumatra or Singapore when captured and made a prisoner of the Japanese. He died on 10th October 1943 aged 23. The fact that he is buried in Chungkai War Cemetery just outside Kanchanaburi, Thailand, means it is likely he was put to work on the infamous Burma Railway although I cannot in any way confirm this.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website states:

The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma (Myanmar).

Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma, worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre. The Japanese aimed at completing the railway in 14 months and work began in October 1942. The line, 424 kilometres long, was completed by December 1943.

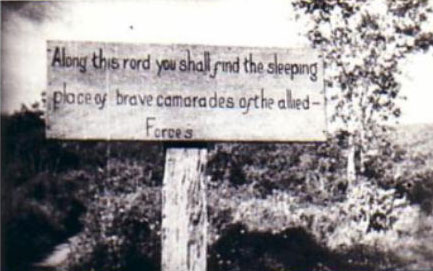

The graves of those who died during the construction and maintenance of the Burma-Siam railway (except for the Americans, whose remains were repatriated) were transferred from camp burial grounds and isolated sites along the railway into three cemeteries at Chungkai and Kanchanaburi in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar.

Chungkai was one of the base camps on the railway and contained a hospital and church built by Allied prisoners of war. The war cemetery is the original burial ground started by the prisoners themselves, and the burials are mostly of men who died at the hospital.’

(cwgc.org)

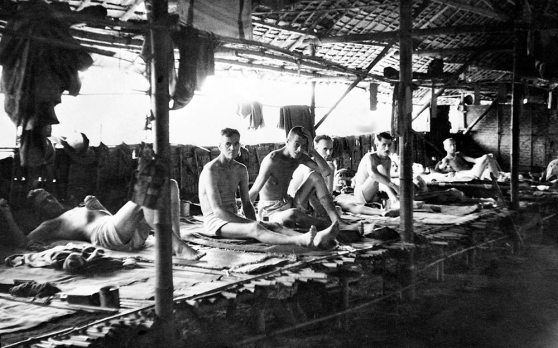

Whether he worked on the railway or not, life under his Japanese captors would have been brutally hard. The prisoners were starved and beaten. Illness also killed thousands of men in the heat and unsanitary conditions. Malaria and dysentery were rife and the medical staff had no medicines to treat the men. Malnutrition was also a major problem which led to weakness and sickness and the men suffered from beri-beri and scurvy.

A personal account of the fighting in Singapore before it was captured by the Japanese has been written by a survivor, Jack Caplan who was a Signalman in the same division as Peter. (ww.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories)

I volunteered for army service on 10 March 1940 and joined the Royal Corps of Signals (18th Division), my number being 2591725. I was then 26 years old. (Peter’s army number was 2595680)

The twice-daily bombing of the island, plus artillery barrage by both sides and continual machine-gunning and trench-mortar fire from the enemy was continuous. Added to the bedlam and utter confusion was the daily attacks by Jap patrols on ‘easy’ targets, such as Alexandra hospital. They entered that building… bayonetting doctors, nurses and patients on operating tables; raped every female unfortunate enough to be caught; anyone in their path was shot dead.

Jap patrols were expert in psychological warfare. They killed with impunity… regardless of sex, age or race. They were able to strike where and when they wished, even though we outnumbered them by at least ten to one they could not be stopped. They were extremely ruthless, and seemingly unafraid of death.

Jack was taken to Thailand and put to work with thousands of others building the railway line from Burma to Thailand. The men were used as slave labour, were not fed properly or given any medical help.

I have witnessed the execution of prisoners – by shooting and decapitation. Also hundreds of beatings and acts of torture…. for no apparent reason. As POW’s we lived in perpetual fear: sans adequate food, water, clothing, bedding, drugs, medicines etc etc And enforced hard labour seven days per week, i.e. twelve hour days of slavery on the Bridge over the Kwai and the Death Railway. This I assure you…we envied those who died.

Peter is commemorated at the church of St John the Baptist, Clayton where the war memorial takes the form of a lych gate and the names of the dead are inscribed on a plaque.

Peter Keys parents never knew of his place of burial. Hilda long hoped for a miracle .

LikeLike

Hi Rob, welcome to the site. It must have been so hard for parents not to know where their sons were buried. It sometimes took many years for their bodies to be brought in from the actual place of death, and possibly a hurriedly dug grave, to an official war graves cemetery. Are you related to Peter Key?

LikeLike